December Staff Picks: Favorite Recipes

posted: , by Elizabethtags: Library Collections | Recommended Reads | Adults | Seniors | Art & Culture

Visions of sugar plums may or may not be dancing in our heads…but with the arrival of winter this month, we’re thinking of a few of our favorite recipes and cookbooks from the stacks! Here are some ideas for comfort food, holiday dishes to share, or a simple recipe to warm a snowy eve.

_____________________________

Carrie’s Picks

I love cookbooks! I love to read them like novels, savoring the language and feasting with my eyes. The Joy of Cooking (seventh edition) by Irma S. Rombauer, Marion Rombauer Becker, and Ethan Becker is the only cookbook I still own. It is taped up, spilled upon, shoved full of hand written recipes and cherished family favorites, and generally looks ready to explode into a million scattered pages. But I love this book! Sushi rice? There’s a recipe. Vegan chocolate cake? Check. Absolute best way to roast a whole chicken? Done! Detailed, descriptive, and containing at least one recipe for nearly anything you may want to make, the Joy of Cooking (seventh edition) is everything a comprehensive cookbook should be.

But if there was one cookbook on my wish list it would have to be The Forest Feast for Kids: Colorful Vegetarian Recipes That Are Simple To Make, by Erin Gleeson.

Beautiful photography of ingredients, procedures, and completed recipes will help children understand what it takes to create balanced nutritious meals, and help them find recipes that include their favorite foods. Vegetarians rejoice, this whole book is for you, but never fear omnivorous friends, you can add any protein you want to the many inventive meal plans. Portobellos and polenta are two of my families go-to vegetarian main courses, and I am always on the lookout for new ways to present these old favorites. Putting them together sounds totally dreamy, and doable! Substitute your favorite cheese, or leave it out altogether, add more onions (please) or use red cabbage instead of Brussels sprouts. The possibilities, and pictures, are appetite inducing.

Whether you go for scholarly tomes like the Joy of Cooking, or visual delights like The Forest Feast for Kids, gather together around a great cookbook this month and create a new family favorite.

Jessie’s Pick

Baking in America: Traditional and Contemporary Favorites from the Past 200 Years by Greg Patent includes so many terrific recipes and is fascinating reading as well. Patent weaves historical notes in among the detailed recipes for Parker House Rolls, California Forty-Niner Cake, and Apricot Coconut Walnut bars, the recipe that earned him second prize in the junior division of the Pillsbury Bake-Off when he was 18. Every time I open it I learn something new about historical baking. Did you know that in colonial times less affluent hostesses sometimes rented pineapples by the day to serve as exotic, extravagant centerpieces? Or that “chiffon” style cake was invented in the 1920s by an insurance salesman who sold his secret formula to General Mills in 1947?

Patent includes tales of his own baking history as well, like his family’s tradition of making fresh donuts on New Year’s Eve. Taking this as inspiration, for a birthday party I once made his updated version of Eliza Leslie’s Doughnuts (1851) and invited guests to fry their own, although we skipped the old-fashioned rose water flavoring and went with vanilla instead. They were a hit, and those who were in attendance years ago still occasionally mention those doughnuts with fondness. Patent’s love of baking shines on every page, his precise research is impressive, and his methods won’t fail you.

_____________________________

Meg’s Picks

Here are few that I go back to again and again:

Nigella Lawson’s Dense Chocolate Loaf Cake is the reason I keep How to Be A Domestic Goddess: Baking and the Art of Comfort Cooking in my personal collection. Add a vanilla glaze and it’s perfect for colleagues’ birthdays: delicious and unfussy.

When I need French onion soup, I turn to Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, because why mess with perfection?

_____________________________

Sarah’s Picks

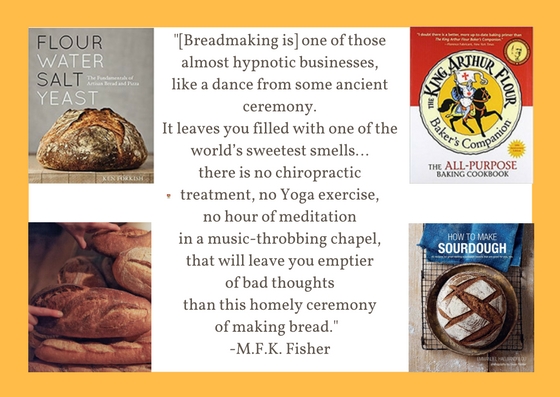

One of my favorite things to do this time of year is bake bread. Nothing turns a house into a warm and cozy home quite like the smell of freshly baked bread. Perhaps it’s the chemical reaction of salt and yeast, or quite possibly it’s the release of the love that goes into mixing, proofing, nurturing, shaping, and baking a loaf of bread. It’s also a relaxing and enjoyable way to spend a chilly afternoon.

I always turn back to my trusty King Arthur Flour Baker’s Companion for tried-and-true classic recipes like Hearth Bread and Honey Oatmeal Bread. This book taught me how to bake bread with its easy, approachable style, explanation of methods, and step-by-step illustrations of important techniques. I’m looking forward to expanding my repertoire with Emmanuel Hadjiandreou’s How to Make Sourdough and sampling a few recipes from Ken Forkish’s Flour Water Salt Yeast this year.

It’s quite remarkable, really, that four simple ingredients can turn into something so satisfying and nourishing. It’s also remarkable how many thoughtful gifts you can create for just the price of flour, salt, yeast, and water. Pair your loaves with one of these Life-Changing Compound Butters and wrap them both up in a swatch of fabric with inspiration from Wrapagami for the perfect gift from the heart!

_____________________________

Gail’s Pick

What if you don’t want to pay more than five dollars every time you want a loaf of sourdough bread with a delicious crusty crust? Ken Forkish comes to the rescue with Flour Water Salt Yeast, explaining how to vary the proportions of these four ingredients to make artisanal bread and pizza dough. This guy has done his homework so you don’t have to. A good how-to book for making great bread.

_____________________________

Raminta’s Pick

My favorite meal of the year is probably my family’s Lithuanian Christmas Eve dinner (Kūčios). I love it more for the traditions, than most of the actual food. My family follows Lithuanian Catholic traditions and therefor, there is no meat or dairy served on Christmas Eve. The dishes served during this meal contain many seasonal root vegetables, mushrooms and lots and lots of fish. Most of us don’t particularly like the fish dishes, but will eat them out of a sense of tradition. Imagine my surprise, after moving to Maine, to find that our primary fish, herring, was used as bait for lobster hauls. The heat of the summer on Commercial Street brings me strange memories.

Over the years, my family has adapted and maybe even cheated here and there. My family down in Florida has added shrimp cocktail for my sister-in-law. My wife brings a pre-meal cheese plate to our celebrations in Massachusetts. On occasion we have even brought down our raclette machine for optimum ooey gooey cheesiness.

Each dish of the evening’s celebrations has special connotations and timing. One of the first dishes of the evening is a simple mushroom broth paired with mushroom buns. The buns are my absolute favorite part of the entire meal. As a child, I would help my grandmother with the preparation and we would make two kinds of buns; mushroom and bacon. The bacon buns were not to be eaten on Christmas Eve, but were to be saved for Christmas. There was NEVER any way that a misshapen bacon bun wasn’t going to end up in my mouth. These buns are fairly simple to make and are seriously so incredibly tasty. My wife and I have been known to make them “out of season.”

Mushroom Buns

- Get a copy of the Joy of Cooking and prepare the dough according to the Parker House Rolls recipe

- 1 cup European mushrooms (porcini are awesome for this) – finely chopped (if using dried mushrooms, rehydrate first)

- 1 small onion – finely chopped

- Salt to taste

- 1 beaten egg

- Sauté onions, mushrooms and salt. The mushroom to onion ration should be about 2 to 1. It really depends on how much you are making. Prepare the dough according to the recipe.

- Take out one small fist full of dough and stretch it out in your palm. Scoop in about one tablespoon of the mushroom/onion mixture and close. You should have a small, football shaped bun in your hand. Brush with egg before baking. Follow baking instructions from Joy of Cooking.

Bacon Buns

- Follow the recipe above and replace finely chopped mushrooms with good quality bacon.

And as my grandmother would tell us, Valgyk!

_____________________________

Jim’s Picks

My mother always made such great baked beans. It’s not usually considered a difficult dish, but you would be surprised how many things can go wrong. Anyway, with my limited talents, the Boston Baked Bean recipe in the Frugal Gourmet by Jeff Smith enabled me to be a successful bean-cook three out of four times.

My one “fancy dish” is from this book as well. That is cooking in parchment: lamb chops in this case. Easy, and it keeps the lamb soooo moist. Also impresses your guests as you present a paper package on their plates with a fully cooked chop inside.

Nate’s Pick

Kenji Lopez-Alt’s fantastic The Food Lab contains more than one recipe for hamburgers. Whether you want to cook a classic, juicy burger on the grill, or a fast-food-style, thin, pan fried one, Kenji has you covered. More than just exhaustively tested recipes, this volume contains a wealth of food science written with the home cook in mind. Lopez-Alt breaks down everything from what cuts of meat to buy at the butcher to how many minutes you should boil your hardboiled eggs for. I also appreciate the relative simplicity of the recipes included; you do not need access to an industrial kitchen to successfully recreate any of the dishes. One of my favorite recipes is for Ultra-Smashed Cheeseburgers, a no-frills take on a classic diner-style hamburger. High on heat and low on handling, this recipe is a go-to for the colder Maine months when grilling outside is a less than enticing option, yet you still find yourself pining for summer flavors.

_____________________________

Elizabeth’s Pick

One snowy eve last winter, while I burrowed with books and blankets, my farmer friend and housemate Sean rustled up a Butternut Squash and Caramelized Onion Galette for a cold-night-comfort-sup, with cherry tomatoes (roasted and frozen in sunnier times) tucked in with the squash to boot. Brown buttery onions, orange squash, gooey warm tomatoes, flaky pastry crust. Holy hot summer. A sweetness and a savory-ness. Reader, we ate it! You can find the recipe in The Smitten Kitchen Cookbook. It works fine to swap flours for a gluten-free galette—that’s what we had.

Wendy’s Pick

Marjorie Standish’s Cooking Down East has been one of my favorite cookbooks since I learned to cook on my grandmother’s huge cast iron stove (what I wouldn’t give to have that stove in my kitchen today!). Marjorie Standish wrote a column for the Portland Press Herald for over 25 years, and this is one of her compilations of her many recipes featured there. The cookbook was well used when I was learning (originally published in 1969 and my grandmother had an original copy) and my current copy is newer but no less well used. It falls open every time to my absolute favorite recipe – Melt-in-your-mouth Blueberry Cake – which, as all of her recipes do, features simple local ingredients. The cake is light and delicious and a family favorite at holidays or just weekend breakfast (side note… it freezes lovely, so make a double batch and freeze one for another day!). It is great for breakfast, dessert, birthdays or just as a snack and is easy to make. My favorite trick that I learned from this recipe is to lightly coat the blueberries with some of the flour before mixing them in; if you do, they don’t sink to the bottom of the cake but stay delightfully distributed throughout. Check out Cooking Down East or any of Marjorie’s other cookbooks for a wonderful taste of Maine – the way food should be…

Eileen’s Pick

Potluck, you say? I’ll bring dessert!

Pie always sounds like a good idea, but it usually looks better than it tastes, in my experience. The crust has to be right. No soggy bottoms. Zigzag edges not so neat as to look contrived, not so heavy as to challenge Cousin Mae’s dental work. It ought to be light but substantial, a container that delights the senses. It has to be easy enough for a mere mortal to make and be proud of.

And, please, the filling should be worth the trouble of making the crust. The whole thing, above all else, should taste better than good.

Pie: 300 Tried-and-True Recipes for Delicious Homemade Pie by Ken Haedrich (2004) will help you accomplish all that. With his many side notes and plenty of practical advice, you are bound to get it right.

Nothing I have run up against in my dessert-eating life has ever made me consider saying, “This is too sweet.” That means that I am happy to engage a generous slice of pecan pie any time. A few holidays ago I had a hankering for just that and swooned, in a focused-research way, over scads of pecan pie recipes before finally settling on Haedrich’s “Louisiana Browned-Butter Pecan Pie.” I bought the required dark corn syrup, knowing that it would sit in my fridge forever, 1/2 cup shy of full. I used his recipe for “Basic Flaky Pie Crust”, followed his directions for successful prebaking, and set to browning the eponymous butter for the gorgeous, gooey innards. Without going into too much detail (that’s what recipes are for) I will say the resulting pie was as close to perfect as I am likely to come, ever. One great crust, a pecan-stuffed filling easily meeting the crust’s high standard, and we had some serious pecan pie that made me think maybe I’d have further use for that leftover dark corn syrup after all, and sooner rather than later.

_____________________________

Hazel’s Picks

For further reading, here’s a book list from our collections: Favorite Feasts and Everyday Meals. You’ll find new cookbooks, plus links to our Cookbooks from Maine list, holiday cookbooks, and more.